We are not dinosaurs

2014-06-26

This post by Peter Sefton is licensed under a Creative Commons CC by license

My recent trip to Europe started with the week-long Open Repositories 2014 and ended with the one day Disruption in the Publishing Industry: Digital, Analytics & the Future in Edinburgh. I suggested to my colleague Peter Murray-Rust and others interested in scholarly publishing tech in general that we hold a technical meetup the day before the publishing meeting. After some back and forth in email PMR took the lead and came up with an event Hackday 2014-06-19 in Edinburgh - a radically new approach to Scholarly Communication in the Digital Enlightenment . Cameron Neylon of PLOS could not attend but sponsored the event with lunch and Mark Macgillivray of Cottage Labs / University of Edinburgh found us a nice room in the Informatics Forum.

PMR has a prestigious Shuttleworth fellowship to create the ContentMine .

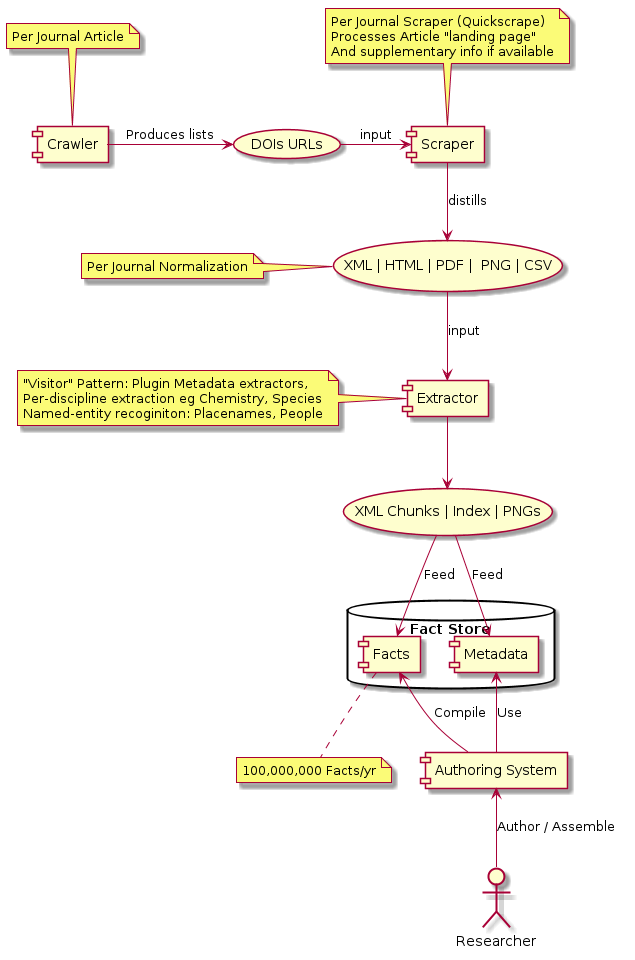

Content mining uses machines to automatically extract and interpret content from the literature. This requires several steps (for which we are gathering and opening the technology):

Crawling: Machines iterate over the content, creating a list of resources (e.g. indexes of scientific articles).

Scraping: Each resource is scanned for content or links to content, which is downloaded.

Syntax: Non-semantic content (e.g. PDF or (ex)propriatory formats (e.g. DOCX)) are converted to a common representation (XML, SVG, XHTML, PNG).

Extraction of Semantics. Machine-learning or heuristic methods are used to extract semantic information from more primitive representations.

Discipline Semantics and Visitors. Specialised tools (e.g. for species or chemistry) extract the science from the XML.

Public Streaming. All extracted content is open and will be streamed to the world.

My main interest in this is from the point of view of authoring tools. PMR and team are showing how using heroic coding efforts they can pull apart PDF files, extract text and diagrams and work out how to parse common types of chart and graph and turn them into meaningful machine-readable stuff, such as parsing drawings of molecules into Chemical Markup Language. These processes are painful, and in the current century should not be needed at all. Why don't we have research and authoring tools that make all this laborious extraction unnecessary? I'll come back to that below.

For summaries of the day see:

- The write up from the Edinburgh Library blog by Claire Knowles:

Our aim for the day was to extract dinosaur facts from open access publications. After an introduction by Peter Murray-Rust, University of Cambridge, we were provided with coffee and set to work.

-

Peter Murray-Rust's blog post . He says:

So now it's official - content mining is fun!. You'll remember we were going to

-

SCRAPE material from PLOS (and other Open) articles. And some of these are FUN! They're about DINOSAURS!!

-

EXTRACT the information. Which papers talk about DINOSAURS? Do they have pictures?

-

REPUBLISH as a book. Make your OWN E-BOOK with Pictures of DINOSAURS with their FULL LATIN NAMES!!

About 15 people passed through and Richard Smith-Unna and Ross Mounce were online. Like all hackdays it had its own dynamics and I was really excited by the end. We had lots of discussion, several small groups crystallised and we also covered molecular dynamics. We probably didn't do full justice to PT's republishing technology, that's how it goes. But we cam up with graphica art for DINOSAUR games!

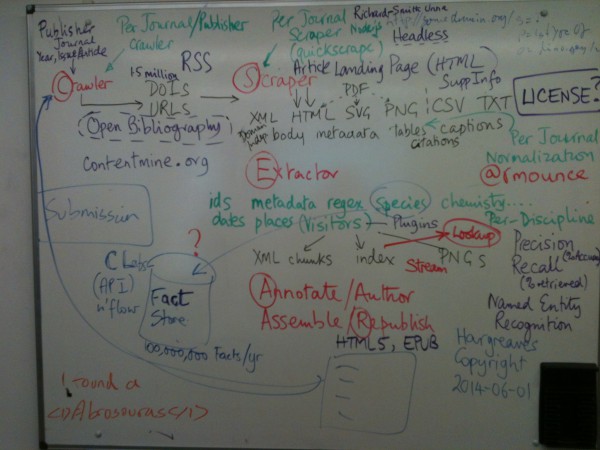

We made huge progress on the overall architecture (see image) and particularly on SCRAPING. Ross had provided us with 15 sets of URLs from different publishers, all relating to Open DINOSAURS.

-

The mining process

Over the day we covered a whiteboard with the mining and refining process:

Whiteboard

Whiteboard

My simplified version:

It's clear that the ContentMine project architecture is working; it is indeed possible to run the various crawlers and scrapers etc to automatically read the literature, but results will vary widely across disciplines. For Chemistry there are good content parsers that can recognise not just mentions of chemicals but reactions and methods, but in a more general field like dinosaurology all we are really extracting is the fact " this paper mentions http://live.dbpedia.org/page/Velociraptor", still useful but not a huge advance over text indexing. It would be much more useful if we could extract, say information about the distribution of species from articles, but that's a much harder problem.

How to side-step the mining process - The Express Lane

So we showed on the hack day the process of scraping lists of document identifiers, fetching the docs and extracting species names is working pretty well.

But what if the species names were baked-in? What if our authoring systems helped us to identify the science in scientific publications, and allowed publishing of data & code rather than diagrams?

For the purposes of this hack day, we decided that a good trial would be to take our extracted facts (dinosaur names) and create a simple Scholarly Markdown document that could be used to write a commentary on the extracted material, but with built-in semantic markup. Take this article for example http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049 .

The abstract says:

The new species , Saurolophus morrisi , is diagnosed by the possession of a postorbital having ornamentation in form of wide oblique groove on jugal process. Placement of this new species in Saurolophus considerably expands the distribution of this genus, although this referral is arbitrary since phylogenetic analysis places the new species outside of the clade formed by Saurolophus osborni and Saurolophus angustirostris

There's a scraper that can extract the species by looking for one or two italicised words. But what then?

If we look up Saurolophus angustirostris it has a wikipedia page and both Saurolophus osborni and the new (in 2013) Saurolophus morrisi have pages which redirect to the genus .

Using the content mine we could:

-

Upon finding something suspected of being a species, look up Wikipedia/dbpedia and other databases.

-

Where there's a match, store the occurrence of the species in the article in the Fact Store.

-

Where there's no match, add that to a "New Species?" alert. Imagine, citizen scientists could watch this list, check out the potential new species and add them to Wikipedia. (Do people already do this via some other mechanism?)

-

Create a stub blog post for new species, so a dinosaur or frog blogger could enthuse about or critique the work.

We nearly got a kind of demo working, but didn't quite hook up all the pieces. Kim Shepard worked on some code to take extracted species names and turn them into a markdown doc like this. It's just a list of links, around which you could tell a story:

[Saurolophus morrisi][1]

[Saurolophus][2]

[Saurolophus osborni][3]

[Saurolophus angustirostris][4]

[1]: http://ontologize.me/?tl_p=http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject&triplink=http://purl.org/triplink/v/0.1&tl_o=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus__morrisi&tl_s=http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049

[2]: http://ontologize.me/?tl_p=http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject&triplink=http://purl.org/triplink/v/0.1&tl_o=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus&tl_s=http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049

[3]: http://ontologize.me/?tl_p=http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject&triplink=http://purl.org/triplink/v/0.1&tl_o=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus_angustirostris&tl_s=http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049

[4]: http://ontologize.me/?tl_p=http://purl.org/dc/terms/subject&triplink=http://purl.org/triplink/v/0.1&tl_o=http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus_osborni&tl_s=http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049

But the links aren't just links. What is this weird looking URL?

If you follow it , then you get to this page that says something like:

The work http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049 is about http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus_angustirostris

Hey! That's a fact! Mined (more or less) from the literature. Thanks to the magic of triplinks (which I invented) we can encode an RDF statement in a single URI, and use it in a markdown document, mail it to people, even use it in Microsoft Word! But the triplink is not (yet) an accepted standard, so what we really want to do is turn that into a standard HTML via RDFa. So, at the workshop I wrote a quick filter for the wonderful pandoc document processing framework, which parses those weird links and produces this:

new dino

Now we have a 'fact' 'properly' encoded in our stub blog-post which we can confirm by pasting it into RDFa Play :

@prefix dc: http://purl.org/dc/terms/ .

http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2011.0049 dc:subject http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saurolophus__morrisi .

See the github project triplink for more info. Note that while these tripley-links are a bit hairy they have advantages over 'proper' RDFa which typically requires authors to have technical skills and access to the HTML source of what they're writing:

-

They can be machine generated by bookmarklets or by websites - eg ORCID and Creative Commons could publish author and license triplinks, and articles could have a 'cite me' link people could copy and paste.

-

They work in any authoring tool, including word processors, email and text editors.

-

Even if you don't have the tooling (such as a pandoc filter) to process them into HTML they're still clickable (provided I keep looking after the ontologize.me resolver)