So here are my semantically rich[1]^ notes for the presentation. This is neither a tutorial nor a coherent story, so you may want to leave now, but there is a picture of Tim Berners-Lee about half way through.

Why embed data in web pages?

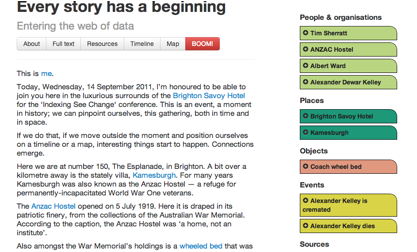

You can make new things happen. Let other people or machines do things with the data. Here’s an example by Tim Sherratt showing how data embedded in the page (left) can drive new behaviour (the stuff on the right).

What is this Schema.org?

(I have added a couple of tags to discuss later)

Many sites are generated from structured data, which is often stored in databases. When this data is formatted into HTML, it becomes very difficult to recover the original structured data. Many applications, especially search engines, can benefit greatly from direct access to this structured data. On-page markup [#inlinedata] enables search engines to understand the information on web pages and provide richer search results in order to make it easier for users to find relevant information on the web. Markup [#semanticsyntax] can also enable new tools and applications that make use of the structure.

A shared markup vocabulary [#sharedvocab] makes it easier for webmasters to decide on a markup schema and get the maximum benefit for their efforts. So, in the spirit of sitemaps.org, search engines have come together to provide a shared collection of schemas that webmasters can use.

http://schema.org/

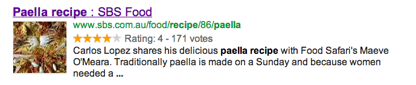

Use Schema.org – get snippets

For data journalism and research, we presumably want to get the data out in a form that it can be reused so the concerns are different – you want the data to be used, and your part in its collection or creation to be cited.

The other thing you need to know about: RDF

RDF is the Resource Description Framework.

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a family of World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)specifications [2]^ originally designed as a metadata data model. It has come to be used as a general method for conceptual description or modeling of information [#sharedvocabularies] that is implemented in web resources, using a variety of syntax formats [#semanitcsyntax].

Now it’s time to over-simplify the process of getting data into web pages via schema.org et al.

Putting data on the web?

-

Is it in some kind of web ready format?*

-

Yes: Put it on the web as-is #justpublish

-

No: Make it into a web ready format. Options:

-

Reformat to a spreadsheet or something #justpublish

-

Embed the data in human readable HTML

#inlinedata and #semanticmarkup

-

Publish as a stand-alone RDF resource**

-

-

-

In any case publish a web page about it***

-

Include metadata in the web page. #pagelevelmetadata

-

Make the metadata standards-based and proper****. #sharedvocab

-

Choose a syntax for the embedding #semanticsyntax

The fine print

*What is a web-ready format depends on how much of a pedant you are – for some only gold-plated RDF is good enough

**And, you know, keep the web page UP.

*** At Tim Berners-Lee’s talk in Melbourne that night David Flanders asked him what advice he had for researchers re data – should they put it on the web?

Tim’s response was that researcher should work with their data in the format that suits them but they should get a ‘shim’ or adaptor built to provide an RDF interface to the data so others could use it as part of the semantic web.

I think that’s easy for Sir Tim to say and he’s right that it would be a Good Thing, but experience has shown that projects like that run to about $200K in Australia and don’t always get results, so I’d add “and while you’re working on the RDF adaptor, publish what you have in the format in which you have it with as much metadata as you can manage”.

****Good luck. If anybody comments at all it will be to ask “why didn’t you use the European/ISO/W3C Standard” (which will turn out to be a document that has been in development for 5 years but expected to be released in six months for the last four of those years)

Figure 1 Tim Berners-Lee (right) dwarfed by the happy head on a sponsor's banner, which in turn is dwarfed by Art - at the University of Melbourne

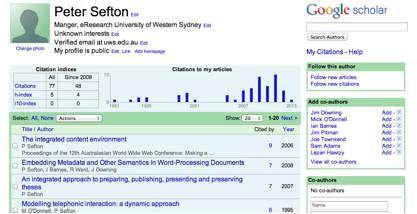

Google Scholar

Case study Getting a scholarly work into Google Scholar

-

A repository somewhere advertised the existence of the work via extensive use of the venerable meta-tag. #page-level-metadata

-

Google found the data, entered it in its database.

-

When you search it puts the metadata back in the page so other software can scrape it out #microformats*

*Microformats mean

Worst-case: maintaining a web-load of converters – see this from a patch to keep the Zotero reference manager working with Google Scholar. Google changes their page? You change your code and redeploy to millions of people.

'//div[@class="gs_r"]/div[@class="gs_fl"]/a[contains(@href,"q=related:")]') + '//div[@class="gs_r"]//div[@class="gs_fl"]/a[contains(@href,"q=related:")]')

These are XPath expressions looking in the webpage for stuff that Google coded for their own reasons, probably to make it look right, not primarily for data interchange.

Sounds like a case for Schma.org?

You’d certainly think so.

But don’t underestimate the power of commercial interests to distort the shape of the semantic web.

There are (at least) two things to be standardised in web semantics

-

The (hopefully) shared vocabulary / world view - “ontology” #sharedvocab

-

The encoding method; how the meaning is embroidered on to the web #semanticsyntax

And of course we have multiple overlapping but incomplete standards, best practices, worst practices and flame-wars for both.

Four ways to #inlinedata

-

Metadata about a whole page via meta tags in the head #pagelevelmetadata #traditional

-

Metadata/data about parts of a page: #semanticsyntax

-

Microformats (obsolete but persisting) using conventions #byconvention

-

Microdata – part of the (non W3c) HTML5 spec simple, flawed, controversial #worksbutpissedpeopleoff

-

RDFa - obscenely complicated unless you use RDFa 1.1 lite #theonetrueway

-

\

[3]^ Semantically rich? Look at the source – I’ve used a web-police-approved mechanism for embedding slides in my prose. That is, I have used a standard vocabulary (the bibliographic ontology #sharedvocab) and a syntactic specification (RDFa 1.1 lite #semanticsyntax) for saying that some parts of the page are special.