First, lets look at the HTML that drives this, then I’ll come back to

how you author it, and how you get it to display, and why this matters.

In an HTML document mark up any block level (container) element you’d

like treated as a slide to say “This is a slide”, by referring to The

Bibliographic Ontology.

rather than one of the standard

mechanisms for HTML semantics, and as far as I know none are designed to

mix slides with other content.

What’s wrong with <div class=’slide’>?

-

It’s a mere convention.

-

Slide is a noun that sometimes means things other than the parts

of a Powerpoint presentation.

-

And it’s a verb too.

-

We can do better using microdata or RDFa structures and a

standard ontology to say “This section here, this is a slide”*

* Feel free to start a debate in the comments about whether it says

that really says this is a slide or is about a slide. You can refer

to this, which

will make everything much clearer.

My aim is to produce documents that are independent of the systems used

to store, serve and process them, hence the declarative approach. You

can drop one of these documents into any CMS or processing tool and it

will behave as normal HTML. But a system which is aware of the semantics

can do something special with the content. To demonstrate this I have

written a very small WordPress plugin which you should be able to see in

action here in this post, and in my previous post, [on collaboration

around research

data](http://ptsefton.com/2012/09/12/virtual-infrastructure-and-research-support-fostering-collaboration-across-institutions.htm).

Slidyfy Wordpress plugin; initial, crude modus operandi

-

Look for slides; elements of type

http://purl.org/ontology/bibo/Slide

-

Wrap said slides in a border, with a link to view slideshow in new

window. Then in new window:

-

Build a new <body> element with just the slides.

-

Replace existing Body with new slides-only version.

-

Load the W3C Slidy CSS and Javascript.

TODO: Support some of the other presentation engines.

-

Result: user sees slideshow.

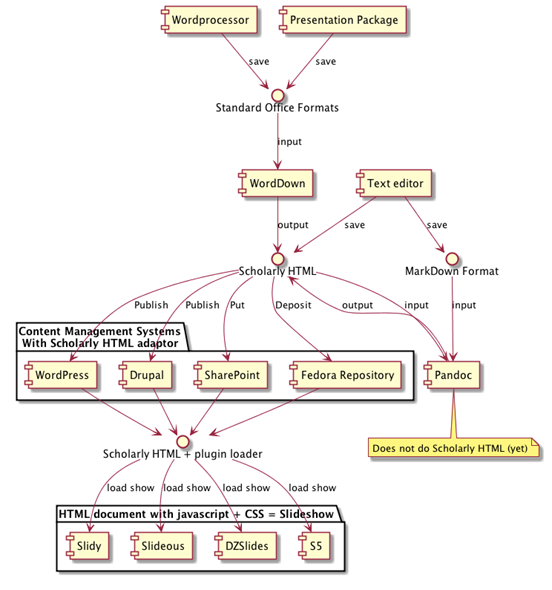

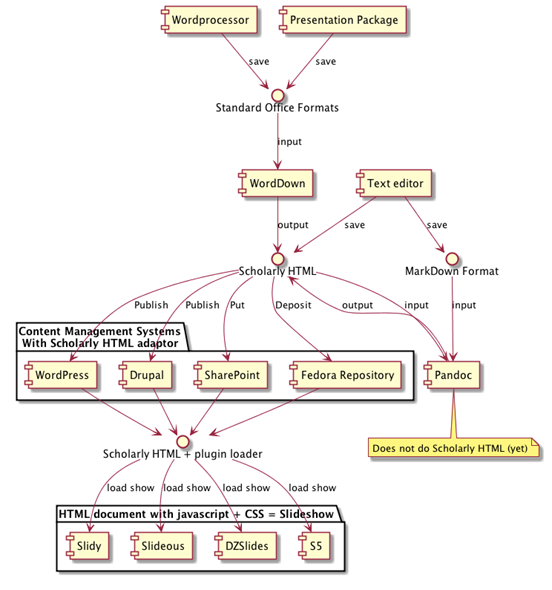

Authoring Workflow Separating content from delivery

How would someone use this? Well, they’d reach for their Scholarly HTML

editing environment. This might be a text editor, where they’d make HTML

documents by hand, or they might work in Word or Open Office Writer, or

PowerPoint or a combination of both (more on that later) via

WordDown. Or, if

they were prepared to do a little work coding they could use something

like Markdown, which is

one of the family of Wiki-like markup languages.

Asciidoc is another. Or, this

could be done in an online content management system like WordPress or

SharePoint or something. None of these are really that convenient for

many users, but then strangely there is no really convenient way to make

good HTML.

The important part is to separate content from the delivery

mechanism.

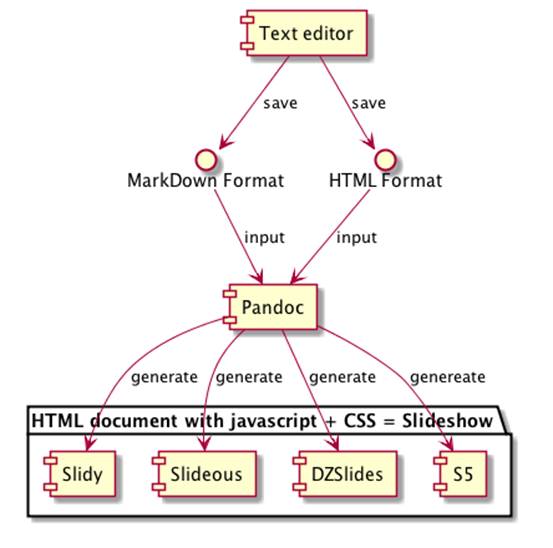

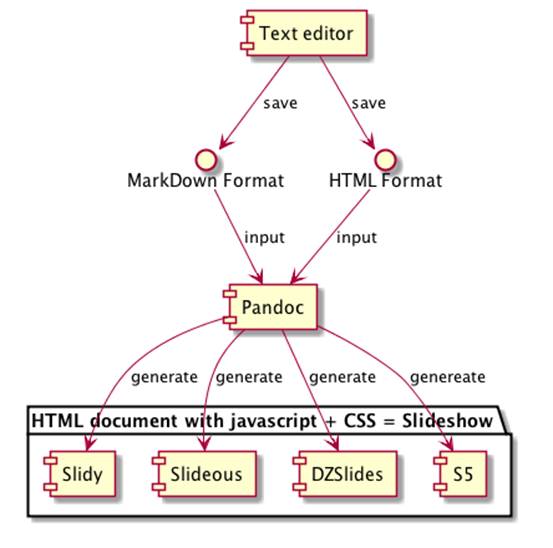

Right now, if you want to make a presentation for the web, it’s pretty

hard to beat Pandoc. It takes Markdown format or HTML and makes

slideshows. This is not quite what I want in my use case, but it’s on

the right track. Pandoc automates taking plain-old content and making it

into a slideshow using your choice of HTML-based slideshow systems. Most

of these systems require you to author not just a specially formatted

HTML document but to include one or more scripts and CSS stylesheets,

and Pandoc takes all the hard work out of that. You just can just give

it either Markdown or HTML with headings and you’re away.

But, the result is still useful only for stand-alone documents for

people who are prepared to use command line tools and have access to a

web server, or run the slides from their local machine. It would be next

to impossible to post the result as a WordPress post for example. And it

doesn’t allow mixing free-form document content with embedded slides.

The Pandoc approach – full marks for separation of content from presentation*

*Pun intended

As far as I know, though Pandoc and the Markdown format it supports

don’t recognise embedded semantics via RDFa 1.1 or Microdata. That’s

something to look into, and I’ll be exploring that in work we’re doing

at the University of Western Sydney on embedding references to data in

publications, because we want to be able to refer to data sets and code

etc in research articles and README files, and a text-based markup

language may well be ideal for authoring those.

Anyway, Pandoc’s nice but it’s not what we’re after here, which is

something that runs in the content management system, or at time of

viewing.

Some workflow options for making Scholarly Slides

Why?

This is not just about one person’s hopefully harmless fetish for mixing

up blog posts with slides; there are lots of things that go on the

scholarly web where embedding semantics is important.

One example I have looked at before is chemistry – to embed a

visualisation of a molecule you don’t want to have to hand-code the code

to load, say, the JMOL molecule viewer applet into a page, and leave it

on the web – JMOL will get updated, and may be obsoleted, it would be

better to try to use a more future-proof declarative markup.

To illustrate this see a previous post of mine with a plugin to show a

3D

molecule.

When I started writing this something had broken in that plugin caused

(I think) by a new version of the jQuery library, so the page just

showed a link to a CML file instead of the molecule viewer. This is the

whole point of using declarative markup. The pretty part broke but the

science didn’t.

Another example which I don’t think anyone has yet done in HTML +

Semantic markup would be to format a research article into its parts.

Instead of slides, you’d be marking up Method, Abstract, and Results et

al.

Reasons this kind of technique is important

This allows us to:

-

Control and host or own stuff (cf embedding a slideshare player)

-

Produce long-term maintainable web documents that may degrade but

will still be readable

-

Continue to build the semantic web*

-

Improve indexing and discovery

-

Pave the way for robots to read and process documents

*Even if we don’t believe in it

****

Copyright Peter Sefton,

2012. Licensed under Creative

Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Australia.

<http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/au/>