There are three points they wanted me to speak about in a session about Fostering Collaboration. When I decided to do this, I thought it would be relatively easy, this is right up my alley. But as I started preparing, I started telling myself a slightly different story that I thought I would. So, here are my notes for tomorrow, complete with dodgy embedded slides.

Fostering Collaboration across Institutions

-

Improving the collaborative capacity of research data

-

Making data discoverable and connected

-

Security and IP

Of course the technicalities are important and in some other contexts it would be hard to stop me from going on about them but for this topic, fostering collaboration I’m going to focus on the people and think about how the systems and data serve the people.

Remember, data don’t collaborate…

… people collaborate.

(Tip: Never mind cats, don’t ever try to herd someone who’s half sheep dog)

There are two kinds of people

-

Researchers

-

And people who are here on earth to help them

At UWS, we have started mapping out these relationships and there will be a lot more of this.

I have a lot of experience with collaborative projects both in the Higher Education world, and in open source software. I’ll start with some of the techniques that I have found to work. One of the basic things is to pay attention to what’s working for other people, and not just your immediate peers. The best people to watch are the ones who get stuff done.

Q: Who knows best how to run huge collaborative knowledge management and generation projects?

A: The people who built a substantial part of the Internet, the Linux operating system and invented various kinds of ‘open’.

Watching the Alpha Geeks

Tim O’Reilly said in 2002:

So often, signs of the future are all around us, but it isn't until much later that most of the world realizes their significance. Meanwhile, the innovators who are busy inventing that future live in a world of their own. They see and act on premises not yet apparent to others. In the computer industry, these are the folks I affectionately call "the alpha geeks," the hackers who have such mastery of their tools that they "roll their own" when existing products don't give them what they need.

The alpha geeks are often a few years ahead of their time. They see the potential in existing technology, and push the envelope to get a little (or a lot) more out of it than its original creators intended. They are comfortable with new tools, and good at combining them to get unexpected results.

What we do at O'Reilly is watch these folks, learn from them, and try to spread the word by writing down (or helping them write down) what they've learned and then publishing it in books or online. We also organize conferences and hackathons at which they can meet face to face, and do advocacy to get wider notice for the most important and most overlooked ideas.

I started applying this back in 2006. The RUBRIC project was about Regional Universities Building Research Infrastructure Collaboratively – a circa $6M project from 2006-2009 to establish institutional repositories in a variety of Australian and New Zealand universities. I was the technical lead on the project, but the project manager went on maternity leave very soon after the project started and I ended up as de facto manager for a good while.

To help establish the collaboration between a dozen or so universities and associated bodies such as the National Library and ARROW and APSR, I tried setting up a project collaboration area using Trac, which is a Free tool developed for and by software developers. Trac has a wiki, and a ticket management system, and was used to house the code that generated on the project. We also used online bookmark manager Delicio.us to compile collaborative lists of resources, Zotero for compiling a shared bibliography, held phone based teleconferences and even had SharePoint available for those who could bear it not to mention a static website.

We gave our cohort of between ten and twenty collaborators (it varied) access to all these systems and let them use the bits that suited them. Different sub-groups tended to hang out in different parts of the system; most were exposed to new tools they could take away with them to future endeavours, I know that members of the RUBRIC central team at least took away knowledge of ‘alpha geek’ tools and attitudes that have helped them since.

Please, walk on the grass

I learned a couple of things about building useful working relationships in distributed teams.

-

Face to face day-long meetings with dinner the night before and a decent hotel work better than tense teleconferences.

-

Subsequent teleconferences work well, but repeat (1) as needed.

I asked Amanda Nixon, who is now my counterpart eResearch Manager at Flinders in South Australia what she leaned from the RUBRIC project about collaboration. She said that building interpersonal relationships was important, not relationships based on roles.

Personal attributes of an Alpha Collaborator:

-

Shows up

-

Speaks up

-

Keeps up

-

Blogs / publishes

-

Can operate as an individual, not a role

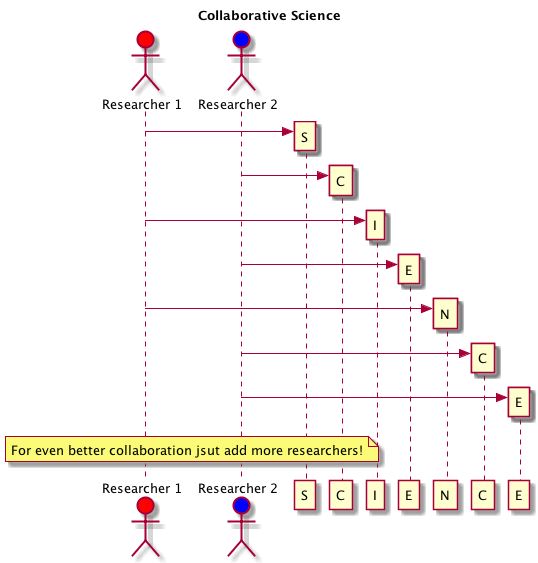

After talking with Mat, I out together a jocular ‘model’ of research collaboration. This shows two researchers creating “science” by taking turns to make parts of the whole. This is similar to something I put together for my PhD that showed two people collaboratively creating T E X T one letter at a time. While these simple diagrams might seem a bit silly, in Systemic Linguistics in the early 90s there was an important point to be made – all the models of collaboratively produced text were expressed as flow-charts, that is they were synoptic rather than dynamic models.

Point is, we need to be careful in modelling and thinking about collaboration to make sure that we think in dynamic models that do take into account the various participants and stakeholders.

Collaborative research model v0.1

After extensive ethnographic research on @MatToddChem at pub last night: my model of collaboratively doing science pic.twitter.com/2E4hkK47

Contribution from Mat

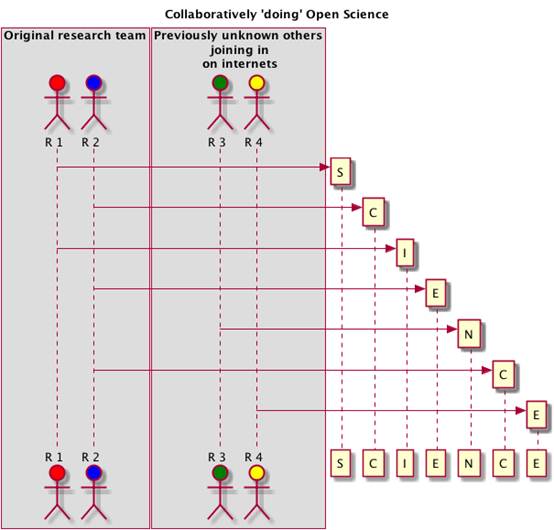

@ptsefton most interesting. If it's open, one does not need to define, in advance, who the researchers are. #openscience

@MatToddChem Too hard given my skills with diagramming tool

.@MatToddChem But seriously, I gathered openness of data & process and advertising via social networks were key success factors

@ptsefton Correct, meaning that anyone can join, including people you don't know at the start, outside regular circle.

An _open_ collaboration model v0.1

**

**

An example of open science

In April 2010 a request was posted to a (closed, 2,500-member) process chemistry networking forum^12^ on LinkedIn for suggestions, but also for people who might be willing to contribute more materially. This stimulated 20 comments (from 11 different people) and four private e-mails (via the website**). None of these contributors were previously known to us.** From the advice and offers, we chose to send one gram of racemic PZQamine to a Dutch contract research organization, Syncom, which arrived in mid-May. On 25 May, the company posted the identification of several chiral columns and conditions that enabled the baseline separation of the PZQamine enantiomers, permitting an assay for the effectiveness of any resolution attempts. On 25 August the company posted a lead chiral acid that had been identified (actually two months earlier) that effected the resolution of PZQamine. The company was not paid for this work.

Woelfle, Michael, Piero Olliaro, and Matthew H. Todd. “Open Science Is a Research Accelerator.” Nature Chemistry 3, no. 10 (2011): 745–748. http://www.nature.com/nchem/journal/v3/n10/full/nchem.1149.html

(Speaking of outmoded forms of communication, Mat also talked about the value of traditional conferences – we don’t need them to communicate any more, so why not use face to face time to focus on getting word done, via workshop meetings that attack particular problems.)

In Australia, we’re now operating in a policy framework which is trying to encourage re-use of data, and open publication, but we’re stuck on hamster-wheel which is apparently hooked up to electrical generators which keep the lights on at Elsevier.

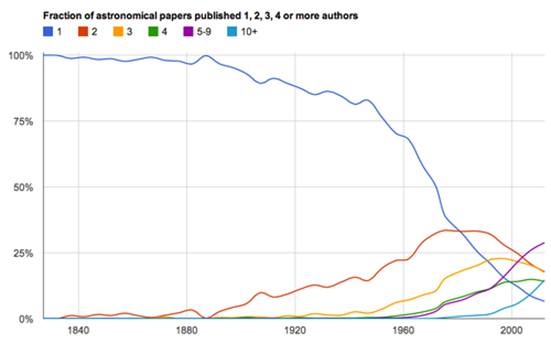

Where can we look for hints about a way off the treadmill? Well, the astronomy and physics communities have made trails. They have been working in teams for years, they publish everything openly at arxiv.org, and being technical, tend to be able to roll-their own tools.

**

Another community of alpha-collaborators

Fraction of astronomical papers published with one, two, three, four

or more authors. CREDIT:* *Robert

Simpson**

http://radar.oreilly.com/2012/08/data-mining-the-literature.html

At this point I’d better get back to the data.

Making data collaboration-ready

All we have to do is get data sets into RDA, right?

ANDS-wins

The latest ANDS newsletter has a number of success stories about data-driven collaboration. Read it.

Example from the ANDS newsletter

Repository of Antibiotic Resistance Cassettes

The repository ([www2.chi.unsw.edu.au:8080/rac](file:///\vmware-host\www2.chi.unsw.edu.au\8080:rac)) allows researchers to submit data on potential cassettes online. This information is reviewed by staff at the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, and any new cassettes are provided with accurate names, archived and the knowledge made available. The database can then be searched online and the cassettes annotated from anywhere in the world. At present, it has regular users in 15 countries, though primarily in Australia.

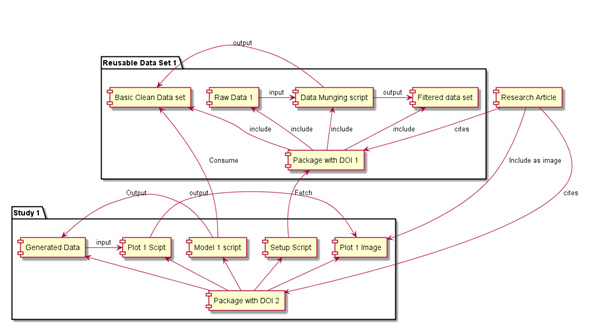

To understand what kinds of systems we need to support collaboration around data reuse, we need to talk in detail to large numbers of research cohorts in a wide variety of disciplines. I have started with such project with researchers at the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment. At this stage I am working with climate modeller Remko Duursma on getting some examples of how environmental data can be packaged for re-use, with complete provenance to show how raw data is cleaned, filtered, fed to models, and used to generate figures for research articles. Remko and I will broaden this out to a wider range of participants once we get some initial demonstrations sorted out.

We have to work out how to carve-up the continuous process that these researchers go through of taking raw data, cleaning it up, using stuff like “known good days” when the facility was known to be operating correctly, using a reproducible well documented process, filtering that data down to something useful and then running various processes over it and publishing the results. What should be packaged together? What’s useful for others? What’s dangerous to release on its own (like raw data with known bad parts).

Nascent UWS project: Reproducible Research publications

(Sorry, but it’s complicated)

Making data linkable – give everything a URI

Actually, I do have this to say about security. Given the state of infrastructure we have, data can be in one of two security states it’s either open to all, or locked down so that only the repository admins and the researcher can see it. More complex collaboration requires a mature community with their own resources

Please, don’t say “IP”

Richard Stallman was probably more concerned with capital-F Freedom than with collaboration, but his insight that copyright could be turned 180° created the conditions for a huge collaborative engineering effort to create a vast free software stack created by O’Reilly’s alpha geeks. Stallman’s insight was possible because he looked at the mechanism of copyright, the legal framework, rather than the illusion of “intellectual property”, the vague association of the properties of physical property with a notional abstract virtual property.

Don’t talk about “owning” data

Use language appropriate to the various kinds of intellectual property that researchers are dealing with.

Making data collaboration-ready?

-

The alpha-collaborators are telling us Remove all “IP” related issues by using open licenses or go public-domain.

-

If that’s not possible, seek tools that allow the right people to work together.

(Thanks NeCTAR with your cloud and labs and tools) -

Do data management well. Eg use linked-data approached to metadata.

(Sorry if you were expecting that talk, maybe next time)

-

And finally:

If in doubt and you need a collaboration tool: use a mailing list.