Digital Object Pattern (DOP) vs chucking files in a database, approaches to repository design

2014-09-21

At work, in the eResearch team at the University of Western Sydney we've been discussing various software options for working-data repositories for research data, and holding a series of 'tool days'; informal hack-days where we try out various software packages. For the last few months we've been looking at "working-data repository" software for researchers in a principled way, searching for one or more perfect Digital Object Repositories for Academe (DORAs).

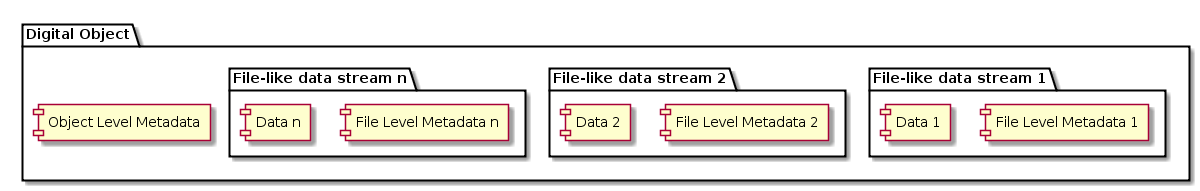

One of the things I've been ranting on about is the flexibility of the "Digital Object Pattern", (we always need more acronyms, so lets call it DOP) for repository design, as implemented by the likes of ePrints, DSpace, Omeka, CKAN and many of the Fedora Commons based repository solutions. At its most basic, this means a repository that is built around a core set of objects (which might be called something like an Object, an ePrint, an Item, or a Data Set depending on which repository you're talking to). These Digital Objects have:

- Object level Metadata

- One or more 'files' or 'datastreams' or 'bitstreams', which may themselves be metadata. Depending on the repository these may or may not have their own metadata.

Basic DOP Pattern

Basic DOP Pattern

There are infinite ways to model a domain but this is a tried-and-tested pattern which is worth exploring for any repository, if only because it's such a common abstraction that lots of protocols and user interface conventions have grown up around it.

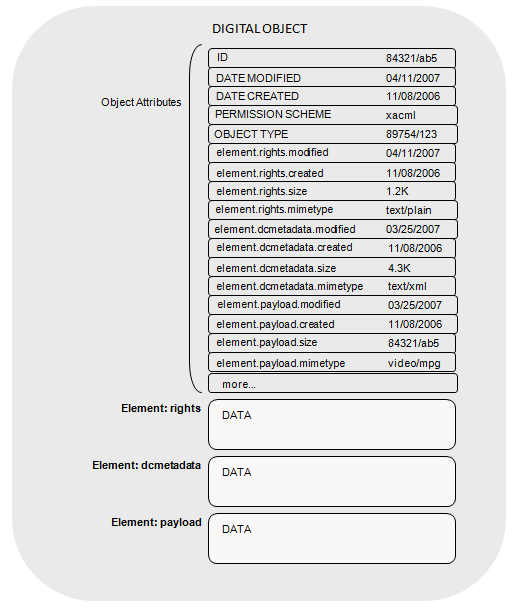

I found this discussion of the Digital Object used in a CNRI, Digital Object Repository Server (DORS), obviously a cousin of DORA.

This data structure allows an object to have the following:

a set of key-value attributes that describe the object, one of which is the object's identifier

a set of named 'data elements' that hold potentially large byte sequences (analogous to one or more data files)

a set of key-value attributes for each of the data elements

This relatively simple data structure allows for the simple case, but is sufficiently flexible and extensible to incorporate a wide variety of possible structures, such as an object with extensive metadata, or a single object which is available in a number of different formats. This object structure is general enough that existing services can easily map their information-access paradigm onto the structure, thus enhancing interoperability by providing a common interface across multiple and diverse information and storage systems. An example application of the DO data model is illustrated in Figure 1.

To the above list of features and advantages I'd add a couple of points on how to implement the ideal Digital Object repository:

- Every modern repository should make it easy for people to do linked data. Instead of merely key-value attributes that describe the object, it would be better to allow for and encourage RDF-style predicate / object metadata where both the predicate and object are HTTP URIs with human-friendly labels. This is implemented natively in Fedora Commons v4. But when you are using the DOP it's not essential as you can always add an RDF metadata data-element/file.

- It's nice if the files also get metadata as in the CNRI Digital Object, but using the DOP you can always add 'file' that describes the file relationships rather than relying on conventions like file-extensions or suffixes to say stuff like "This is a thumbnail preview of img01.jpg"

- There really should be a way to do relationships with other objects but again, the DOP means you can DIY this feature with a 'relationships' data element.

(I'm trying to keep this post reasonably short, but just quickly, another really good repository pattern that complements DOP is to keep separate the concerns of Storing Stuff from Indexing Stuff for Search and Browse. That is, the Digital Objects should be stashed somewhere with all their metadata and data, and no matter what metadata type you're using you build one or more discovery indexes from that. This is worth mentioning because as soon as some people see RDF they immediately think Triple Store, OK, but for repository design I think it's more helpful to think Triple Index. That is, treat the RDF reasoner, SPARQL query endpoint etc as a separate concern from repositing.)

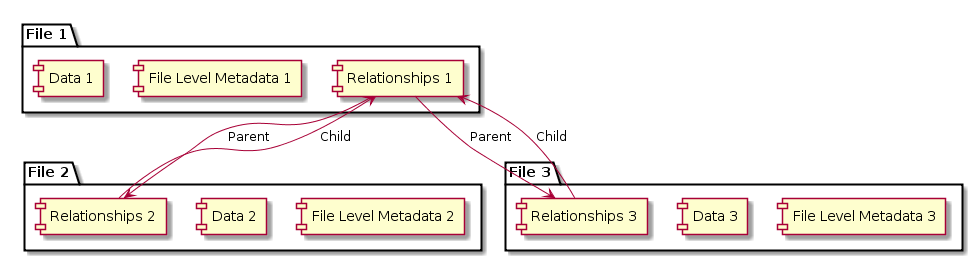

The DOP contrasts with a file-centric pattern where every file is modelled separately, with it's own metadata, which is the approach taken by HIEv, the environmental science Working Data Repository we looked at last week. Theoretically, this gives you infinite flexibility but in practice it makes it harder to build a usable data repository.

Files as primary repository objects

Files as primary repository objects

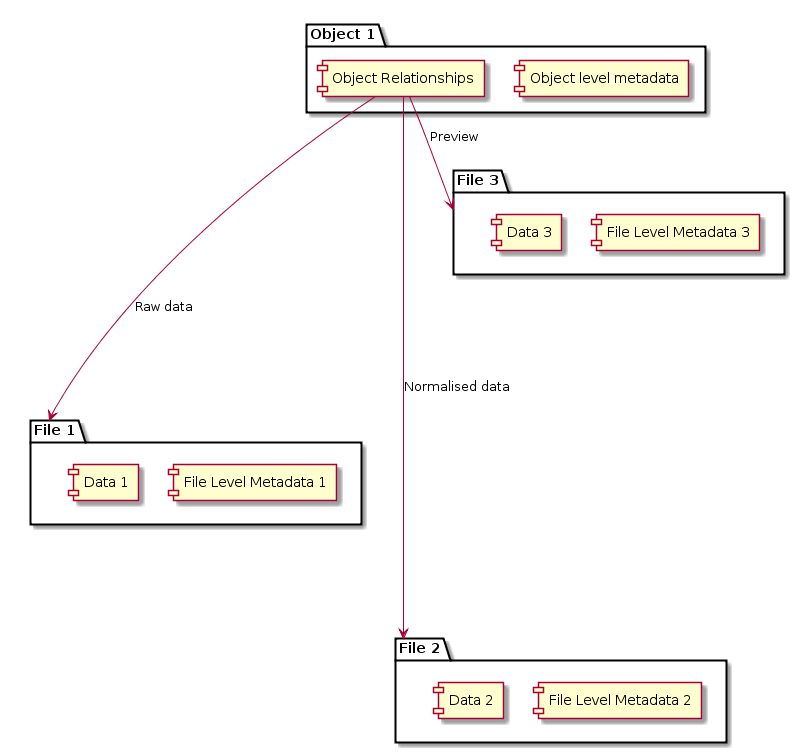

Once your repository starts having a lot of stuff in it like image thumbnails, derived files like OCRed text, and transcoded versions of files (say from the proprietary TOA5 format into NETCDF) then you're faced with the challenge of indexing them all, for search and browse in a way that they appear to clump together. I think that as HIEv matures and more and more relationships between files become important then we'll probably want to add container objects that automatically bundle together all the related bits and pieces to do with a single 'thing' in the repository. For example, a time series data set may have the original proprietary file format, some rich metadata, a derived file in a standard format, a simple plot to preview the file contents, and re-sampled data set at lower resolution, all of which really have more or less the same metadata about where they came from, when, and some shared utility. So, we'll probably end up with something like this:

Adding an abstraction to group files into Objects (once the UI gets

unmanageable)

Adding an abstraction to group files into Objects (once the UI gets

unmanageable)

Draw a box around that and what have you got?

The Digital Object Pattern, that's what, albeit probably implemented in a somewhat fragile way.

With the DOP, as with any repository implementation pattern you have to make some design decisions. Gerry Devine asked at our tools day this week, what do you do about data-items that are referenced by multiple objects?

First of all, it is possible for one object to reference another, or data elements in another, but if there's a lot of this going on then maybe the commonly re-used data elements could be put in their own object. A good example of this is the way WordPress, which is probably where you're reading this, works. All images are uploaded into a media collection, and then referenced by posts and pages: an image doesn't 'belong' to a document except by association, if the document calls it in. This is a common approach for content management systems, allowing for re-use of assets across objects, but if you were building a museum collection project with a Digital Object for each physical artefact, it might be better for practical reasons to store images of objects as data elements on the object, and other images which might be used for context etc separately as image objects.

Of course if you're a really hardcore developer you'll probably want to implement the most flexible possible pattern and put one file per object, with a 'master object' to tie them together. This makes development of a usable repository significantly harder. BTW, you can do it using the DOP with one-file per Digital Object, and lots of relationships. Just be prepared for orders of magnitude more work to build a robust, usable system.

Digital

Object Pattern (DOP) vs chucking files in a database, approaches to

repository design is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License.