Repositories! (What are they good for?)

Georgina Edwards has invited me to Intersect NSW to give a talk to the software engineering team about repositories in eResearch. There were also quite a few eResearch analysts in attendance, not to mention a couple of members of the senior management team. (Just in case you’re wondering, the answer to the question in the title is not “absolutely nothing”).

Here are my notes, with embedded slides, which I put together on the

train to and from the CBD (ie quick and dirty).

The summary: repository means a lot of different things, but the main sense I talked about with the Intersect team was ‘data-store component’. I tried to cover why using a repository in an eResearch project might be important because repositories can provide a lot of ready-made functionality, particularly in the area of digital preservation, but also access to indexing services and content-transcoding to generate new formats from things ingested. I talked about one aid for thinking about repository services which I think is useful – the Repository Micro-services framework from the California Digital Libraries, and ran through some of the repository frameworks that people in the eResearch.au world might encounter.

The liveliest discussion was around RDF, the Resource Description Framework, and what it’s good for. I made the assertion that RDF was the best practice approach to storing metadata, allowing for built-in extensibility. RDF uses URIs as names for both things and relations, which reduces ambiguity and aids interoperability. But I think it’s important to draw the line between RDF as a good way to do metadata, and annotation and the assumption that an RDF query language (via an RDF triple-store) is always going to be needed or even work. I’m sceptical about the promise of RDF as some kind of super semantic world-wide web of knowledge you can query for the answer to anything, but it’s clearly a good way to do metadata – there’s no excuse for inventing a new metadata schema that is not RDF based these days. (Use the comments if you want to discuss).

The talk

I thought I’d start from something that the developers would be familiar with. Source-code repositories.

To a bunch of software developers…

… a repository is a place to put code

What’s a repository to me?

The first time many of us heard the term repository in Higher Education was in connection with the Open Access movement, when a few forward thinking universities in Australia QUT, UQ, USQ and even some others outside of Queensland began to set up Institutional Repositories, using software like Eprints or Dspace. These were essentially online databases of PDF files for academic works, with bibliographic metadata. They were also seen as sites for preservation of materials, and had services to advertise their contents to the world, via the OAI-PMH metadata harvesting standard, and via metadata embedded in the web pages that described the academic works.

A group of us put together a presentation for Open Repositories last year on the growth of Institutional Research Data Repositories, alongside the ‘traditional’ Institutional Publications repository.

There are a few senses of the word:

-

Repository-as-database

-

Repository-as-application

Institutional Repository or Data Repository

-

Repository-as-lifestyle (ie analogous to a ‘library’)

With that in mind, the point of this discussion: is what might a repository-as-data store be good for in an eResearch project?

Services in a typical repository-as-datastore underneath an application:

-

If the app goes away the data is/are safe independently of the application services,

-

with all digital objects stored in standard formats

-

with standardised metadata

-

so they can be preserved*.

-

-

You get OAI-PMH (pull/out) and SWORD (push/in) built in

-

Built in security/access control

(but beware of actual real-world performance)

-

Content transcoding

(thumbnails / image viewers / video versions)

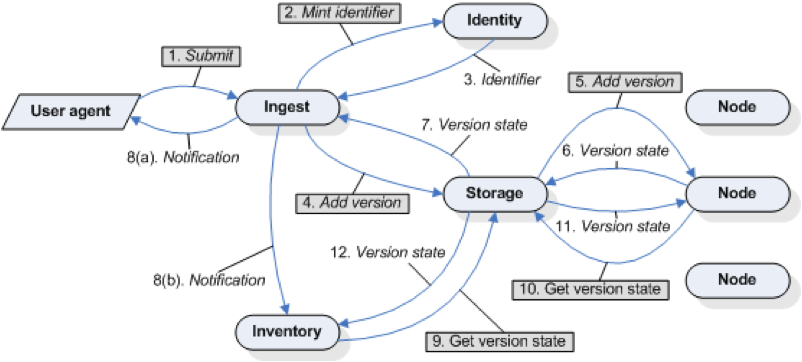

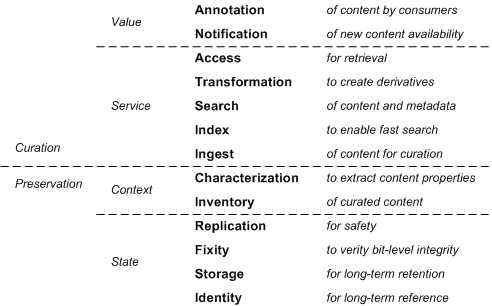

The Repository Micro-services framework from the University of California captures all these services really nicely.

Repository Micro-services

http://journals.tdl.org/jodi/index.php/jodi/article/view/1605/1766

This is implemented in http://merritt.cdlib.org/, which does not seem to have an obvious application to download.

Repository micro-services

Some repository software you may hear about

-

Eprints (Perl)

Good for publications repositories, has been used for cultural collections, learning – has every imaginable interface to repository content

-

DSpace good for a range of digital object collections

eg Andrea Schweer’s talk on a data capture app Building a repository for freshwater quality data

-

Fedora Commons (back end)

-

Islandora application/platform (Drupal PHP)

-

The Fascinator platform / ReDBOX Application (Java + Jython)

-

Hydra platform (Rails)

-

-

CKAN – a Research data Hub app (Python)

-

Micro-service components like BagIt for packaging and PairTree for efficient file-storage.

NOTE: All of the above apart form Eprints include built-in search using Apache Solr.

The basic answer is that if in the long run your project is going to require some large percentage of the repository micro-services discussed above, then you’re going to end up writing your own Fedora-like thing. Also, I think it’s better to be part of a community looking at these things together. For example Fedora is not a magic solution to being able to re-use repository content between applications, but it is reassuring to know that the Hydra and Islandora communities are talking about interop via their Hylandora project and there is a significant amount of preservation-work happening in the Fedora world.

To some of us, the idea of doing certain kinds of eResearch project without a back-end repository (as in something that has managed services around preservation under some kind of serious governance) would be like doing software development without a code repository. The question, of course is which kinds of project? And of course, if you do need one, where do you put the repository part in the architecture.