At UWS we’re about to start work on our Research Data Repository project, which you can read about over on the UWS eResearch blog. The starting point will be the Research Data Catalogue component of the repository. The main point of the catalogue is to describe research data collections for the purposes of discovery, reuse, reporting and archiving. But what is a research data collection and how might a researcher put one together?

I won’t attempt an all-encompassing answer to that, but I would like to look at one common case, where a data collection is a set of files. How can we help researchers deal with file-based data efficiently, and as generically as possible?

This is important – we know from talking to eResearch and IT people from other universities that if you provide raw storage to researchers people will use it; it will start to fill-up and at some point the institution will be scratching its eResearch head and asking “what exactly do we have here?”. We really need to get data described both early and often, and to think about data in the context of the research lifecycle; applying for grants, reporting on grants, publishing and so on.

This post tackles the question “How can we help our researchers keep track of the vast amounts of stuff that will start accumulating our servers when we roll out file storage services?” It summarizes a recent demo I gave at Intersect NSW, our eResearch partner, at a meeting organized by Ingrid Mason (@1n9r1d). The demo is designed to show how generic file management services could help researchers to select and package file-based data for easy deposit into long-term curated, managed storage in a couple of scenarios.

I have written about this before, and showed some other Intersect people a similar demo last year in the hope that the demo might be of interest to the team working on the application formerly known as FieldHelper. FieldHelper is about getting files labeled and bundled for repository deposit as efficiently as possible. I’d love to hear from the Intersect team about what other applications they’ve found in this space, and their experiences with The Fascinator software, comments are open below, or there is an active mailing list for the software.

Previously I have shown the same demo software looking at other kinds of data such as computational chemistry in the Beyond the PDF workshop organized by Prof Phil Bourne, and documents, such as Joss Winn’s thesis.

The use-case for a data collection is where there are a number of files that need to be grouped together:

-

A desktop or laptop computer.

-

A workgroup or departmental shared drive.

-

An institutional data storage service.

-

A replicated cloud service like Dropbox or Google Drive.

So, there’s a bunch of data files sitting somewhere; on a laptop, a share, an USB message stick, in Dropbox, etc.

-

Nobody knows what they’re for apart from the people who created/collected them.

-

The university, the researchers, funding bodies, the public, the government, lots of stakeholders want to make sure the data files are looked after; so they can be reused, so the publication can be validated so that others can build on the work, so they can be cited, and archived for the appropriate length of time.

For the data for this demo I chose an example from the University of Western Sydney, where I work, using a data collection collected by Professor Roger Dean and Dr Freya Bailes from the MARCS institute. This data set is one of the exemplars from the university’s Seeding the Commons project, funded by the Australian National Data Service. It’s a collection of measurements of audio intensity in a range of musical works consisting of 51 files, all plain text. This data set is explained in a journal article, A rise-fall temporal asymmetry of intensity in composed and improvised electroacoustic music.

There’s a web application (The Fascinator) watching the relevant storage, finding all the files you put there and showing them to you as best it can through a web browser. There are two ways to package the files:

-

In a hand-curated ‘package’ where you can corral a group of files, optionally provide some navigation hierarchy and describe the data. This was the main focus of this particular demo.

-

In a dynamic view of the working storage that watches the storage for data with certain properties such as a location on disk, a tag, or a metadata field and does something with it, like routing it a repository or a collaboration-space.

The demo:

-

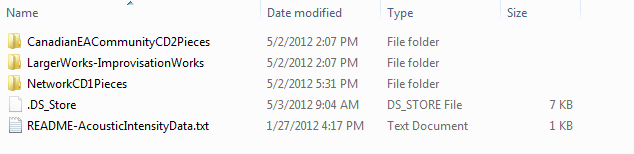

There’s a Dropbox folder (as in dropbox.com) on my machine. I put the sound intensity data files in there:

-

I’ve set up a server using a free (as in beer) virtual machine from the NeCTAR research cloud, funded by the Australian government.

On the server I have installed a copy of The Fascinator in its default, un-customized guise – but remember the same software could be installed on a laptop, or in the lab. (The Fascinator is the Free Software toolkit that was used to build the ReDBox Research Data Catalogue that’s being widely deployed in Australian Universities now, including at UWS).

-

The server also has the Dropbox folder so anything I put in the folder on my machine turns up there (there’s still no compelling Free (as in libre) alternative to Dropbox that I could have used, but we keep looking – has anyone tried OwnCloud or SparkleShare? Let me know in the comments).

-

The Fascinator is, by virtue of a few lines of configuration, watching the Dropbox folder. Anything that appears in the folder gets processed. Metadata is extracted, web-previews are generated for office documents, images, videos etc using an extensible set of plugins. If there was a business case someone could write a plugin for the sound intensity data, to show it as a graph, or do analysis across samples.

-

You can see the files in the web interface via the file system

:

: -

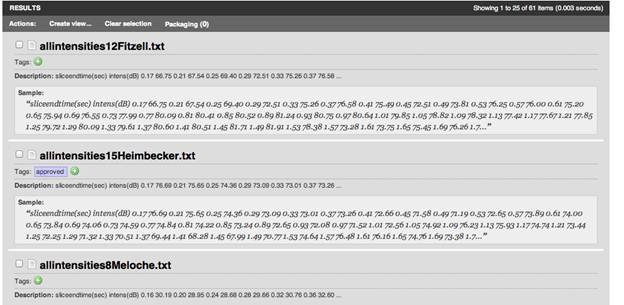

And via a search interface:

-

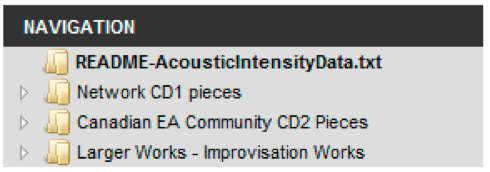

And there is a mechanism to package several files together, and build a navigational structure for them. This produces a navigable package outline.

-

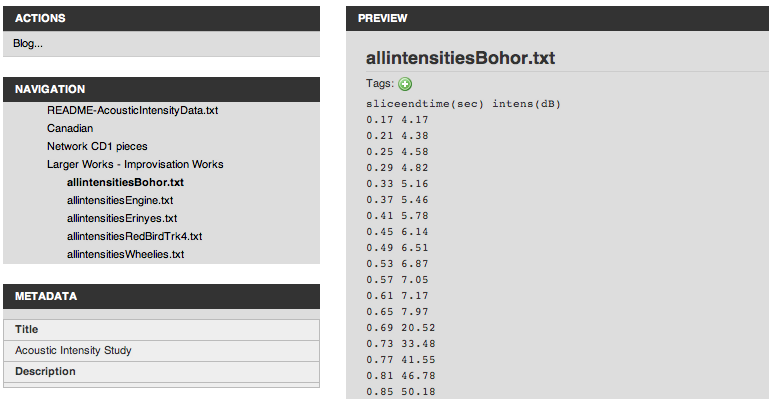

Here’s what it looks like when browsing the package online to find an individual file:

So we have:

-

Found the data.

-

Packaged it together and ordered it.

-

An interface, using The Fascinator where we can eyeball the data file by file, tag things, or apply formal metadata; there’s a huge list of features in The Fascinator, we would need to work out which ones are useful to which researchers if we deployed it in this kind of role.

-

-

The next step is not done yet, but soon we will demonstrate a very simple workflow showing a path from files on disc, to a package in the institutional Research Data Repository. I could tag this package as ‘CurateMe’ and institutional Research Data Catalogue could pick it up and put it in the work-queue for a research librarian to help with long-term curation. This is exactly the same model we described for linking our Data Capture project for ecological data to the Research Data Catalogue.

This work is a demo that was built by the team back at the University of Southern Queensland. The work there was halted, but now with many institutions building institutional Research Data Catalogues with their free ANDS Metadata Stores money it is time to think about how we might capture some of the long-tail research data which is never going to have a $200,000 data capture project devoted to it and how we are going to keep track of data throughout the research lifecycle.

Copyright Peter Sefton 2012. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Australia. <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/au/>